We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

Hungarian National Gallery, Building C, 2nd Floor - 17 April – 21 July 2024

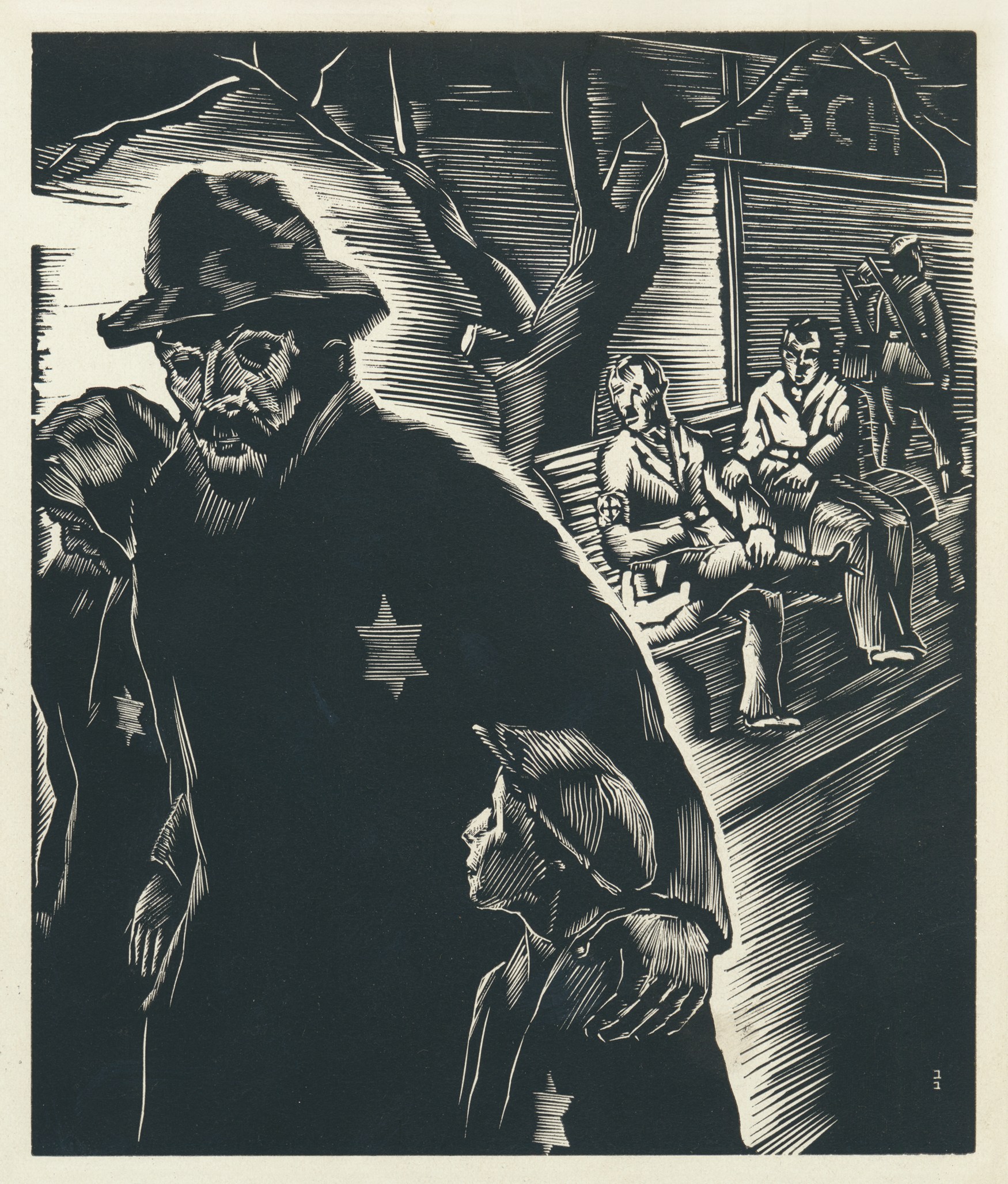

The exhibition is dedicated to the memory of the Holocaust in Hungary, which ended nearly eighty years ago. The displayed drawings, prints, and albums record life in the concentration camps, ghettos and the labour service in narrative, figurative and often comic strip-like works. The representation of the Holocaust in the fine arts, the perspective of the artists who witnessed it, and the artistic documentation of what they saw are crucially important to the understanding and interpretation of the Holocaust, with these works becoming extraordinary mementos through the passing of time and the memories of the survivors fading.

Our exhibition presents works by nearly thirty artists, including Béla Kádár, Endre Bálint, and Ilka Gedő. A great many of the exhibits come from the collection of the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, complemented by works from other Hungarian institutions and from abroad.

Many of the displayed works were produced directly after the liberation with the intention of bearing testimony. While adopting various approaches, all these pieces were conceived through the duty felt by the witnesses. Thus (re)living and “replaying” the events of the past, visitors to this exhibition can be part of the personal and collective processing of trauma. Standing on the borderline between works of fine art, historical documents, and trauma processing, these works did not belong to the Hungarian artistic canon up until now. The albums are personal and intimate, yet they are testimonies to be heard by the whole world.

The exhibition seeks to answer the question of whether personal associations – relating stories in individual visual language, at times with humour or playfulness –, and the appreciation of art itself can be reconciled with the terrors of the Holocaust. How can these means help the processing of trauma? Can art express what words cannot? It is often said that the Holocaust as a subject only appeared in Hungarian visual art long after the end of the war, and even then, only implicitly. However, the works displayed at our exhibition, predominantly made between 1944 and 1947 and virtually unknown to the public, refute the statement that discourse on the Holocaust was treated as a taboo after the war. The series of scenes openly showing the suffering during the war differ in several respects from those works, made in later decades, which address the tragedy of the Holocaust in their titles and/or content implicitly, as part of cultural (collective) memory, in a more indirect and abstract way. The narrative and often brutal comic strip-like series of scenes reveal what happened as mementos, commemorating the events, forcing us to face them and to never forget them.

The exhibition presents drawings, prints, and albums recording life in the concentration camps, ghettos and the labour service in narrative, figurative, and often comic strip-like works. The pictures/albums displayed here were made by the survivors who returned home, based on their personal experiences and often diverging from the artistic style otherwise characteristic of them. This also confirms how profound the feeling of duty was in the artists: putting aside their individual aspirations, they lived up to what is expected of witnesses and documented for posterity the events they personally experienced, at times with the intention of giving testimony, virtually like war correspondents, or as invisible court draughtsmen at a criminal trial.

Guiding visitors through the different sections of the exhibition, what is displayed draws a special picture of the approaches adopted by the artists who witnessed the Holocaust. The first unit presents how artists of Jewish origin experienced antisemitism gaining ground from the mid-1930s and the period of the ever-greater infringements upon their rights. This is followed by works that were made in the ghettos after the Nazi occupation, during the labour service and in concentration camps. A unique characteristic of these works, which were made simultaneously with the events they recorded, is that by drawing these experiences out of their system (”telling” them and processing them through the medium of drawing) the artists not only documented the events, but artistic creation helped them to survive. The next section comprises works that were made in the two to three years after the liberation of the camps. With memories slowly fading, these pieces often become more symbolic and abstract, and in some cases the documentary depiction of events is mingled with metaphors and fictitious scenes. Thus, the concrete images of personal memory slowly meld together with the summarising images of collective memory. The last section of the exhibition has the continuity of the role of witnesses at its focus: survivors, whose works can be seen as visual indictments of the war, veritably became court draughtsmen of court trials, when they made drawings of the accused at the people’s tribunals and the Eichmann trial.

Through the eyes of the witnesses, “experiencing the events with them”, the exhibition guides visitors through the various sections, presenting this tragic period of our history.

Curator of the exhibition: Zsófia Farkas, art historian (Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives)

Edit Bán Kiss studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, then from 1926 continued her sculptural studies at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts. In November 1944 she was driven on foot to Austria and deported to Ravensbrück. It was here that she produced her series of drawings titled Táborélet képekben (Camp Life in Pictures) which was destroyed by female camp guards. After liberation, she reconstructed these drawings as a gouache series titled Deportation, depicting the women’s camp at Ravensbrück. The Deportation series tells, “re-enacts” and processes the events of the camp in a style like children’s drawing, in an almost comic book-like format. It is a significant event that the series from the collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte in Ravenbrück is now on show in Budapest.

Ilka Gedő enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1945, where she studied from Jenő Barcsay. From the summer of 1944 until January 1945, she lived in a yellow-star house at 26 Elizabeth Boulevard. Ilka Gedő’s five sketchbooks were like diaries, documenting life in the Pest ghetto. She drew card players, orphaned children, old people, street scenes – almost taking on the role of an investigative reporter or war correspondent. In her self-portrait, the artist is seen with her lips pressed together and a palette in hand, simul¬taneously analysing herself and documenting events with unquestionable confidence, holding on to this artistic attitude to preserve her dignity.

Ágnes Lukács was born in Budapest, and in 1939, she was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts as the only Jew in her class. In summer 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz. After her return home, she produced a series of ink drawings entitled Auschwitz: Women’s Camp. Her painting, Memory of Auschwitz, was produced decades after the war, and is dominated less by the intention to testify, but rather to present the symbolic, pervasive nature of trauma. It is a painting outside time and space, and the actual place – perhaps this is why the artist chose a subjective colour scheme, similar to German expressionism, reflecting inner reality.

17 April – 21 July 2024

Online ticket purchase